See this show for £6. Use the code OOJ when booking. Performances at Greenwich Theatre on 9, 12 or 14 July Book tickets.

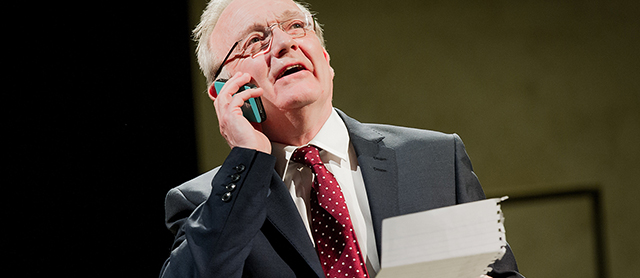

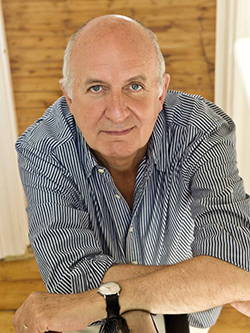

Max Stafford-Clark and writer Stella Feehily are working with students from LAMDA drama school on their final year show – a major rewriting of the “lost” restoration comedy Love and a Bottle by George Farquhar. Here we talk to Max and Stella, and below you can read the experience of one of the young actors, Joseph Prowen.

“We sent one of the students, who plays a beggar, to Finsbury Park station to beg – he wasn’t allowed to come back until he got at least 50p! It took him about three quarters of an hour and he said it was a mortifying experience. But when he came back, he played the scene completely differently”

Max Stafford-Clark and Stella Feehily talk to us about the process of creating Love and a Bottle and working with LAMDA students

What was it about the play made you want to rework it?

SF I’d read Love and a Bottle and loved it. It seemed like the perfect project to work with LAMDA students on. It’s young and full of spirit. The females in it are also resourceful, strong and very, very funny – that’s the other reason I wanted to do it. It’s quite sassy. Max had asked me to do it and I said the only way I would is if I could do it with LAMDA.

MSC Farquhar gives identities to his characters and he also gives them an emotional existence. Stella has done just this through workshopping the piece, especially with a character called Mrs Trudge, who she has since renamed Mistress Endwright. She’s gone from a fifteen line part to having one of the biggest parts in the play. By doing this, Stella has really released a whole emotional strand of the play.

What does the process involve? How do you begin?

SF Well Max has actually worked with LAMDA students before on a verbatim play called Mixed Up North, which was written by Robin Soans. Max and Robin went up north and interviewed locals and that formed the basis of the play. Whereas this project was quite different – I had this ancient text which I had to try and make sense of to begin with. Then I had an idea that because there were so many different characters, it would be best to conflate them all – I cut the character of a playwright named Lyrick and instead gave that role to Roebuck – which meant that we actually brought the play much closer to the autobiographical account of Farquhar’s first visit to London. So by the time we had our first proper rehearsal I already had a draft of this new version. From there, we started to cut the play – it needed to be a lot leaner. Once we’d done the cutting, we went through the process of casting, and once we knew who was playing who, I started to write each character to match the students’ personalities. So the creative process really sprung from the students’ differing personalities and writing each character to suit them. Joseph, for example, is a talented musician, so I have adapted his character Roebuck to play the violin.

How has it been working with LAMDA students?

SF Having the opportunity to knock the piece around with enthusiastic, talented drama students was essential in helping me write this play. I would ask them to do silly things to help me which I perhaps wouldn’t ask professional actors to do; they would run around the room and try out different accents, which really helped me envisage where the energy should be in the scene. Coming from an improvisational background myself, that is exactly what I wanted – for people to say yes, let’s go, let’s try that. They’re such a warm bunch of actors, and we loved seeing them develop so much from the initial readings to seeing them create these gorgeous, hilarious characters and speak the language so fluently and with ease.

We sent one of the students, who plays a beggar, to Finsbury Park station to beg – he wasn’t allowed to come back until he got at least 50p! It took him about three quarters of an hour and he said it was a mortifying experience. But when he came back, he played the scene completely differently; the humility that he brought to it was just extraordinary.

What are the differences between working with student actors and working actors?

MSC I would say it’s very similar. The first job you have as a director is to create a company – and the majority of that has been done for you because you’re presented with a company when coming to LAMDA. The second thing is to be able to harness the actors’ enthusiasm for the project, which has to be led by my own enthusiasm and the ability to turn the energy of discovery into the energy of performance. Immersing the students in the historical background was fun for both of us, and it was a learning curve for me as well as for them.

How important are drama schools in the role of new writing?

MSC Well the facilities are marvellous. Having the opportunity to unearth a hidden gem means we’re also restoring it to the canon and saying this play is worth considering, which will be a considerable service to the whole theatre community that LAMDA has expedited.

“Stella’s created a more well-rounded play, with clearer resolutions and she’s fleshed out the characters”

Joseph Prowen, a graduating BA (Hons) Professional Acting student at LAMDA, tells us about his time working with Stella Feehily and Max Stafford-Clark on a new version of George Farquhar’s Love and a Bottle, showing at Greenwich Theatre on 9, 12 & 14 July.

We began the LAMDA Long Project – an opportunity for students to work with a professional writer and director to produce the first draft of a new play – in our second year. The process essentially involves research, readings, actioning and improvisation. We had a couple of sessions back in January last year, purely to talk about the play and do a read-through with Max and Stella. From there, everybody had the opportunity to read for each part – Max would say ‘tomorrow this will be the cast’, and then it would change every day. You’d then go home, look at the scene you were going to read, think about the character you were going to be reading for and do any relevant research that needed to be done. It’s really lovely to think that the end product of this play will have been made by us, and that Stella took inspiration from improvisations we did in rehearsals. Everyone had a chance to contribute something to each character.

Working with Max and Stella isn’t just an interesting dramatic process; a lot of the preparation was in the historical research. On our first day, Max did a quiz with us – what happened this year? When did this happen? When was this battle? We’d be asked to carry out some research around the period, or about different parts of Ireland – we might be asked to do a presentation on the Battle of the Boyne one week or John Dryden the next. You’ve really got to turn up having done your research, which is great as it encourages you to work hard.

Unlike a lot of new writing that happens, we had a leg up in that we took a play that already existed, Love and a Bottle, which was George Farquhar’s first play. The play is about a young Irishman named George Roebuck, who I play, and is based on Farquhar. When we got it, Love and a Bottle was great – youthful and exciting – but it felt like it needed some work. So what Stella did with us was to rework it and what you will see when the show opens is an amalgamation of Farquhar and Feehily. Stella’s created a more well-rounded play, with clearer resolutions and she’s fleshed out the characters, making them three-dimensional and much more human.

When we perform Love and a Bottle, there will only be a handful of us playing the same part as we were last year in rehearsals. So going into it again this summer has been like entering into a completely different play: workshopping a piece really is an ever-changing process, which I love. It’s such a rare opportunity for an actor to be able to completely immerse yourself in a process like this – especially with funding cuts. This is also our first major collaboration of this scale, which is great as the training at LAMDA is very much geared towards working as an ensemble, so this is something that’s perfect to do. We really felt like a company this year.

Love and a Bottle opens at Greenwich Theatre on Wednesday 9 July in collaboration with Out of Joint. To book tickets please call 020 8858 7755 or book online at www.greenwichtheatre.org.uk

Plays have strange and complex ways of getting written, that often only become clear much later. It was interesting for me to go back to the time I wrote Our Country’s Good as Max Stafford-Clark and I were auditioning recently for his new production. I found myself remembering why some things had gone into the play and even into specific lines.

Plays have strange and complex ways of getting written, that often only become clear much later. It was interesting for me to go back to the time I wrote Our Country’s Good as Max Stafford-Clark and I were auditioning recently for his new production. I found myself remembering why some things had gone into the play and even into specific lines.

Search

Search